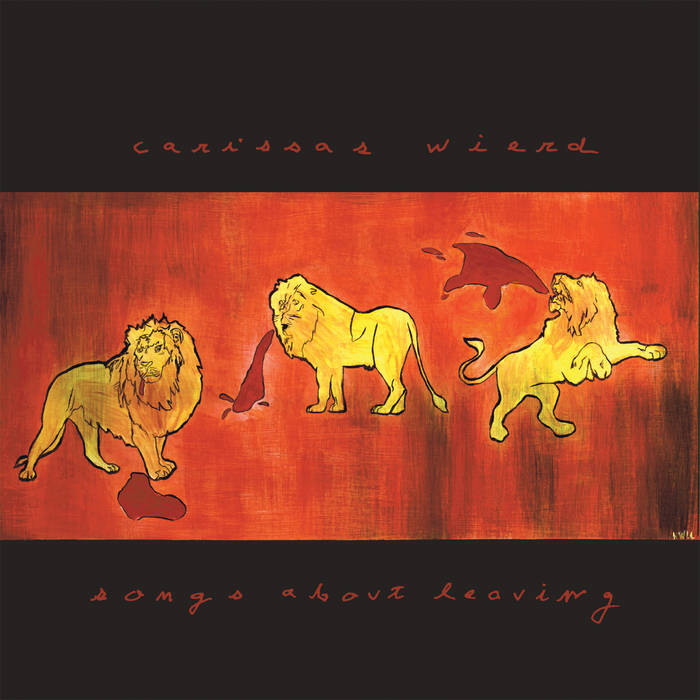

Carissa’s Wierd And Their Beautiful Misery: Songs About Leaving

Carissa’s Wierd And Their Beautiful Misery: Songs About Leaving

by Jack Griffis

Last week’s album overview was about the feelings of dissociation and isolation hidden under a thin layer of outstanding tech-influenced art punk with The Dismemberment Plan’s Emergency & I. This week, were taking a look at an album that does away with any notions of hiding the true melancholia of your lyrics at all, and instead embraces gloom with violin in hand. I of course refer to Carrisa’s Wierd’s final album, Songs About Leaving, one of the greatest slowcore albums of all time and one of my favorite albums to boot.

Carissa’s Wierd (purposely misspelled) were formed in Tucson in 1995 by two teenagers, Mat Brooke and Jenn Champion with very rudimentary equipment, and as much as “spectacular success” can be applied to the small labels and tiny venues of the indie scene, they very much were a spectacular success. Over the course of their careers they released four albums and a handful of compilations and singles, before breaking up to form separate projects in 2003. Frankly, I wish they had stuck around, or at the very least stuck with a record label that would repress their vinyls (because currently they cost 150$ on discogs), but I suppose four unique and emotionally poignant albums is better than a lifetime of mediocrity following their great successes. My buddy Andy put it best when he said its better they don’t burn out and become another case of Weezer-itis. Still, I long for the unique stylings of Carissa’s Wierd, when no other band can scratch the same itch for melancholic Americana-tinged indie music that seems to speak to every soft misery you’ve had to endure. Carissa’s Wierd is funeral music for the living it feels like, not gothic, but rather with a downtrodden folk influence that memorializes waking life and longs for the peace of sleep. And that downtrodden nature is what makes their final album so special– a finale for a band built on the feeling of the living end, a walking death that seems to stick to you no matter where you walk. Its bittersweet, in an odd way, but I suppose all bittersweet things are.

Songs About Leaving would be released on August 6th, 2002, one year before the band’s parting. It was a critical success upon release, scoring solidly on Allmusic, Pitchfork, and SputnikMusic, the latter two giving it a 8.0/10 and 4.5/5 respectively, with Pitchfork remarking that Songs About Leaving was “all the more devastating for being the band’s final act,” a sentiment I find myself sharing every time I give Carissa’s Wierd’s discography another listen, and upon the conclusion of “(March 19th 1983) It Was Probably Green” wishing in vain that there was more. But I suppose that’s the trouble of being conditioned by an infinite slough of streaming sites giving us more seasons to shows no one asked for, more TV show reboots, more Star Wars movies, more MCU “movies” (if they can be called that), the prevalence of the short form video on Instagram Reels and TikTok, and God knows how many other forms of instant gratification– when we’ve got an ending to something beloved, we are never satisfied, never able to take it as a definite ending. But I digress.

My first interaction with Carissa’s Wierd would’ve been roughly when I was 12 or 13 years old while I was on this huge kick of watching student animations or short form animation work– once I had cleared through the large catalog of CalArts student archives (which sadly hasn’t been updated in years the last time I checked), I stumbled upon a Spanish animation, the name of which has escaped me for years now. All I particularly remember is a very tired looking man wandering through his day to day 9-5 grind, with various mundane objects such as street lights and elevators being composed entirely of human beings forced into drudgery and labor unthinkable to us. Everyone was downtrodden and formed entirely of all too pale flesh, and the world around these characters was composed of a limited palette of beiges and browns. It was a bleak, bummer animation that still kinda kicks around my mind when I think about working a 9-5. But what’s important about it was the background track, a track that came from this very album: “So You Wanna Be A Superhero.” A decade and a half since the bands parting, their waves of melancholy and fuzzy vocals were reaching out to a barely-teenager who frankly, just couldn’t get what they were putting down. It would take a few years, but I’d find them again listening to Duster back in 2019 (which I can proudly say I got into them before they became a darling of TikTok some years later), and suddenly the time was ripe to get into Carissa’s Wierd, Red House Painters, Sun Kil Moon, and the wonderfully depressive world of Slowcore. I’d listen to “So You Wanna Be A Superhero” and “They’ll Only Miss You When You Leave” on loop, but given a few more years, I eventually gave the entire record a spin. It’s one of the best musical decisions I’ve ever made. Songs About Leaving is a weight on your chest that keeps on growing heavier with age, a fine wine of melancholia that eats at you with a delightfully corrosive sadness, a sadness exemplified from every note of its instrumentals, to every line in the poetry composing its lyrics. There will never be another Songs About Leaving, which is both a sadness in its own right, and a testament to the once-in-a-lifetime talent of Carissa’s Wierd. Without further ado, I’d like to talk about two songs that exemplify that talent: “So You Wanna Be A Superhero” and “They’ll Only Miss You When You Leave”.

Full of What’s Not Real And Full of Empty Tears: “So You Wanna Be A Superhero”

Sung in the form of a spoken word, “So You Wanna Be A Superhero” comes across as a poetry recitation from inside a dark apartment, the last gasps for air of someone at the end of their rope. Its sound is possessed by this feeling of personal collapse greatly– the vocals are muted, muffled even, sung under a thick fog of despair that struggles to rise over the strumming guitar drowning in eerie reverb that haunts the song. The vocals fluctuate in the song, wavering between something akin to a sob and the muted tone of someone so dejected as to be almost dead in their speech. It’s haunting, the cries of a living ghost, the lyrics containing a desolation not out of place in a suicide note– “So You Wanna be a Superhero” is Carrisa’s Wierd at their darkest, most beaten down.

Carissa’s Wierd, like many indie bands of their ilk, seems to be possessed of a spirit of mystery that compels them to rarely, if ever give an interpretation for their music. To be frank, for something as emotionally charged and poetic as their verses, I think that instinct is for the best. However, in the realm of musical journalism and analysis, I do wish I had the unique input of Jenn Champion and Mat Brooke regarding their haunting lyrics to integrate with my own writing on the subject– but oh well, we are bereft of their literary talents in regards to the origins of their tracks. However, in the case of “So You Wanna Be A Superhero,” what is being discussed isn’t exactly abstract– very clearly this is the chronicle of someone in the chokehold of depression, reduced to very little but isolation and anhedonia, unable to stand such a desolate existence as they reckon with a spiritual hollowness.

The opening lines are stage-setters for the entire song, providing a potent musical image–although we are not told of the subjects circumstances, or given very much information about their life, opening with “There’s banging on the wall/It’s 5 am, I’ve got no sleep at all” gives us a potent image of a beleaguered insomniac, wasting away in bed as the world outside grows in irritating and mind-corroding noise. When listening, there’s a feeling of peering into a life of suffering, a squalid apartment and its anguished dweller, staring at the ceiling with a dead expression. The moaning, dejected voice of Jenn Champion struggles to break through the song, and past the first line, seems only to sink deeper into a soul-consuming malaise, incapable of escape from the internal circumstances that lurk throughout the song. For the protagonist, all of life seems to be a struggle through a mixture of apathetic melancholy and total soul crushing misery– “Too much time in one day/Too much time to occupy/With boring thoughts/And boring moods/And boring bedtimes” speaks to a feeling of utter emptiness, incapable of filling the day with activities that can provide solace from the depressive state that eats at the subject of the song, incapable of finding any joy in life itself– and so everything becomes crushed under a haze of gray, with no joy to be found that could perhaps alleviate this. What drives this home is the following line, “It’s all a joke/It’s all been wrote down by someone who’s probably dead.” There is no comfort to be found in life, no empathy among the living, and so the subject turns her eyes towards the ground– that those who have suffered their fate have long since died, more than likely by their own hand. It is a devastating sentiment of being incurable, that the subject has reached a terminal state of emptiness and lack of interest in life, a living death that only waits for the paradox of her heartbeat to stop.

Rather than dying away in the outro, the songs strumming begins to reach a feverish tempo alongside Jenn Champion’s voice ascending to an apex, a twisted and melancholia-warped shout wherein the only “hope” the song can offer is found– in the phantasms of sleep, the subject dreams of a world in which she may escape her chains of suffocating anhedonia, and perhaps prove some unknown point to her pitiers. She cries out, “ My dreams are full of what’s not real/I’ll fly away and save the world /I’ll make you proud someday/I just won’t be around to see your face,” to a subject “out of frame” as it were. The “superhero” referenced in the songs title is a misguided fantasy of the subject, that perhaps some miraculous strength that will rescue her from her quiet and unending torment, that perhaps she will be able to crawl out of the haze that chokes her life away into a series of late, sleepless nights, and unchanging, miserable days. And yet, even in this fantasy, the presence of death lingers– she won’t be around to see her observer’s pride, and will only meet the fate of death that followed her emotional peers(as noted in the line “It’s all been wrote down by someone who’s probably dead.”). In her only brief moment of hope, the subject still seems incapable of escaping the conclusion that death will take her, the end result of the depressive disease that has stolen all her vitality. The fantasy of sleep provides her only exodus, and yet as she lays awake at 5AM, it seems the solace of dreams grows ever scarcer, and the shape of death grows nearer as morale dies away.

I’m never so bold as to proclaim that my peers were the “best minds of a generation,” as Ginsberg did, but I have seen them consumed by an addictive kind of digital isolation and melancholy that has ruined them for years, the same as he saw his peers destroyed by the influence of heroin. Urged on into their patterns of digital self destruction by years of isolation, first sparked by COVID, then continued out of apathy, they fell deeper and deeper into a pit of online anhedonia– constantly logging in, playing the same games that brought them no happiness, gambling what money they had on cases and online currencies, locked into a cycle of apathetic rage at their circumstances, a faint hope that things might get better, and the complete lack of energy to escape this skinner-box turned skinner-home. It wasn’t their fault. Circumstances as they were, plenty of us sought refuge online– its a time honored tradition, even pre-COVID. Some of us just never escaped that isolation I suppose. I bring none of this up to do an exploitationist “tell all” on those who are stuck behind the screen, but rather to say that 20 years after its release, the tale within “So You Wanna Be A Superhero” still rings true for a generation lost in cyberspace, stuck within digitally-assisted depressive boredom. Only in sleep do some find respite, and others, not at all.

Trying To Find Love Between The Lines: They’ll Only Miss You When You Leave

“They’ll Only Miss You When You Leave,” fittingly titled for the album Songs About Leaving opens on a much more minimalistic tone compared to its sibling songs. Beginning on a simple piano and guitar melody, the song lingers in this quiet space for a while before gradually a violin and quietly grooving drums enter the mix, resting with each other as the song picks up in speed to the strumming of an electric guitar. The violin’s tone, already somber, throws itself deeper into melancholy as the song hangs in the air, bereft of vocals for a while. Suddenly, Mat Brooke’s voice enters and the entire song begins to grow in speed and intensity, rivaling Mat’s voice as he struggles for control auditorily, ultimately exploding into a medley of instruments at full tilt. Taking the same stylistic cues as “So You Wanna Be A Superhero,” Brooke’s voice primarily remains in the form of spoken prose, but his vocals experience a kind of dissonance that surrounds the listener, adding to the overwhelming feeling that takes hold at the songs swelling within the second minute. “They’ll Only Miss You When You Leave,” features all the hallmarks of a great Carissa’s Wierd song, accompanied by the downright solemn violin and downbeat drums that dances with the vocals, and a reverberated guitar that bears heavy musical omens of exhaustion in the face of unending personal sorrow. The pseudo-Americana that Brooks and Champion have incorporated into the band’s wider sound is evident here, living within the folkish rhythms of the drums and the southern gloom of the violin. Electric and acoustic coexist in their suffering, two burnouts sharing a cigarette outside a bus station. To complete this grand work of indie melancholia, Brook’s and Champion’s outstanding lyricism is found in abundance. As I said prior, it seems to almost be THE Carissa’s Wierd song, incorporating all of their stylings and themes into one beautiful mixture of tears and memories of lives no longer lived in.

As “So You Wanna Be A Superhero,” and the rest of their discography, Carissa’s Wierd have an unspoken loathing of speaking on their songs or providing much interpretation (though I imagine if I had a vinyl of Songs About Leaving, the price of which I’ve whinged about previously in this article, its liner notes would be of some use in this matter). And this loathing extends to “They’ll Only Miss You When You Leave.” Nonetheless, the imagery in the song is compelling such that I find that an official “interpretation” would either be useless, or actively detrimental to the song.

The morning opens upon the song as the music swells, regret and despondency dripping off each line as Brooks sings “Not another sunrise, another dry stale taste in your mouth/You walked away from waking up inside of that house,” all seem to speak of a journey, far from what was once home– a refusal to deal with a situation that was draining you of life, another morning spent in regret. At the apex of the song’s introduction, the subject can no longer bear it, and must leave the house– not a home, but “that house,” a place of anguish not fitting of being a home.

The residents of this house are only spoken of vaguely, their emotions taking center stage– “they’ll only miss you when you leave” is spoken only once in the song, but is given great emphasis, overtaking all other sounds. The house is an entity of draining interpersonal strife, and the residents are cruel not in a fantastical sense, but in the sense that their love only extends to when the subject of the song is no longer present. The reality of the song’s subject is not palatable to them– only the idea, only the unseen subject which receives those “postcards with misshapen hearts besides the names.” And within these postcards, these scant messages that carry the subject’s name they “rearranged, analyzed the words/Tried to find something between the lines that wasn’t there,” perhaps searching for love lost or professed, yet never truly there.

One derives the feeling of perhaps an unwanted child, or a relationship that can only be feigned as love when the two are not in each other’s presence, or perhaps a friendship that has withered to very little over the years. Laying within a familiar yet unfamiliar place, a house in which one can find no shelter, the subject awaits a sunrise to give them cue to leave, an action capable of reigniting the feeling of “missing” each other between the two parties. It is a hollow love, one spoken of in letters and phone calls, yet not truly there, kept up for appearances or because the two are unsure what would happen if their neutrality or outright disdain was properly spoken. The final lines of the song “The storm will slowly close in on me/When it’s time to leave” repeated till the instruments finally die away, does not signal one of these incomplete goodbyes, but rather the crushing grip of pretending, the inevitable collapse of the two-sided farce. As the years of only finding comfort when the other is gone begin to take their toll, the storm closes in on the little seclusion and solace one can find, and eventually, that storm destroys the years of falsehoods each party has built. When it’s time to leave, all this will be over, and perhaps both parties of the song will find some peace.

I’ve sat through my fair share of forced smiles and hang-outs at the twilight of a friendship we knew we should’ve both left behind long ago. I’ve had nothing to talk about with people who I’ve known for years. Suddenly Halo split screen and red-40 infused concoctions of soda aren’t enough to keep everyone together. There comes an unfortunate weight of realizing the people you grew up with, who were there for the most formative moments of your youth, more than likely anticipate and enjoy your exit more than they do your entrance. “They’ll Only Miss You When You Leave” cries out to me as an anthem for those who know such things can go on forever, that they can’t lie to each other for much longer. As the passionate flame of youthful friendships subsides into the “once every month if we can” of adulthood, and communications grow more distant, and suddenly you just don’t know what to say to each other while sitting on a couch in a stranger’s home. For one brief moment, the illusion of young adulthood, the feeling of invincibility and a great abundance of raucousness and companionship is broken, and you suddenly feel very, very old. The storm comes, you will send your last text to those you once held close to your chest, and it will be your time to leave. Such is life.

This has been Twin Falls: Music and Memories, and it’s been a pleasure to write on one of the greatest t. I’ll see you next week with another review, and I hope you have a good weekend. And as always, catch my radio show Jacksonville Vice, airing on Spinnaker Radio, 95.5 FM WSKR, 11 AM every Monday (except for next Monday, September 2nd due to Labor Day).